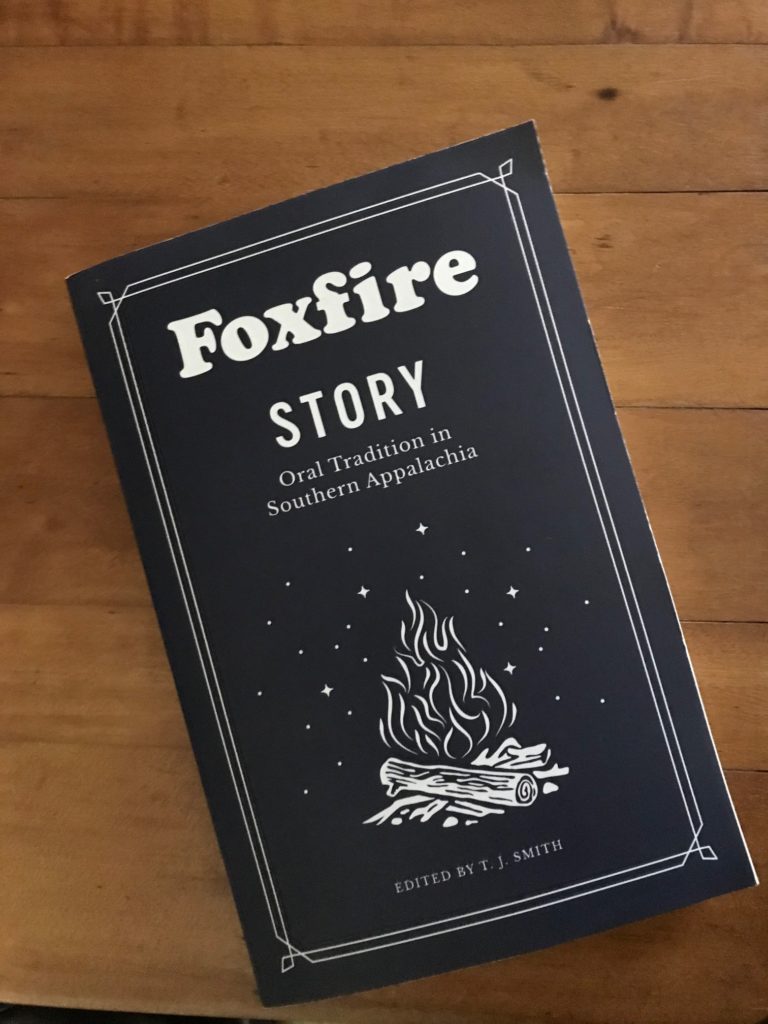

As we approach the long-awaited release of Foxfire’s newest book, Foxfire Story, we decided to bring you a small sample of the folktales you’ll encounter in this volume. Foxfire Story is filled with tales and legends collected throughout the 50+ years of Foxfire’s history. These range from anecdotes about cats getting stuck in wood stoves, hunting tales about dogs and monkeys and bears, legends explaining the origins of names, and haunting tales of the supernatural. Listen in and hear from storytellers May Justice, Pat Cotter, Lyndall Toothman, Will Seagle, and Luther Rickman.

Transcripts:

May Justice

FF: I’ve never seen it.

MJ: You’ve never seen it? When I was a child, there was so much of it, we had it in our house. You know, we–in our house–at night, the fireplace was twice as big as the one over here. And they burned regular logs in it; you didn’t have to split them, you just put them in two, you know. You didn’t have to split them this way. And put ’em in there and the fire never went out from spring ’til next spring. Fall ’til spring. And I can remember that some of that wood, you’d wake up in the night and you’d see this glowin’ there, you know. And that would be that. That was–I learned, that’s just like a …

FF: Yeah, I’ve heard my grandmother tell of things sort of like that. She lives in South Georgia.

MJ: It’s phosphorescent wood, that’s what it is.

FF: Yeah, it’s phosphorous, it’s not called foxfire where my grandmother comes from. But she had an old pond, about way back in her land and my grandfather used to go hunting back there. He scared a bunch of the city cousins one time real good that way.

MJ: I think that the phosphorescence in wood is akin to this that accumulates in the slime of ponds. And then there’s a thing that people, some of the old ghost stories and haint stories that they had, you know, would be this–they’d be walking along and they’d see this mysterious ball bob up and down. Bob up and down, bob up and down. And made from the phosphorescent–and the gasses, you know. And that’s also why it got to, that’s where the graveyard and the stories about the ghosts on the battlefields, you see. It all comes from a form of decomposition. That’s what it is, it’s those gasses that form. And sometimes, maybe when they didn’t bury the bodies too well or something, that there’d be cracks down in the grave, you know. Well, the coffins weren’t very well built, the body might as well have been dumped into the ground. Maybe sometimes in the battlefields, you know, they had to bury the dead very carefully. And later on, they’d–these things that they thought were ghosts over the battlefield, was nothing, were this phosphorescence that came from the gasses from the decomposing bodies. Doesn’t sound nice to talk about it, but that’s what it was. And then that gave a rise to all these legends, that the ghosts were walking over the battlefields and the soldiers had risen from their graves, you know, things of that kind. And that’s, all so much that is legendary has its truth–the tradition on the legendary–it has its spark of truth in reality.

Pat Cotter

PC: Okay, Jack tales are tales that Appalachian people used when they couldn’t explain something to their kids, they’d tell ’em a Jack tale. And it was more of an entertaining process, and there was some truth to it. But most of it was half-truth. But it’d either put the kids to sleep or get ’em off your back for a while. So, the Jack tales–this is a Jack tale that my grandfather told me how the Jack-o-Lantern got its name. There was an old Irish farmer who lived pretty close to him, and he was very, very mean. He didn’t go to church on Sunday, he didn’t go PTA meetings, he was just–he didn’t pay his paperboy. He was just all in all, a bad character. But he did have one attribute that made him famous in East Tennessee. He grew the best apples in the state of Tennessee. On his farm there, he had apple trees. And he grew the best, the biggest and sweetest apples in the state. The governor would come in and get his apples from there. He was just–they were great. And the devil heard about Jack’s apples. And it don’t happen so often now, the devil used to drop in to see people every now and then. And so the devil dropped in by Jack’s house, and said to Jack, “I hear you got the best apples in the state.” And he said, “I have. I’ve probably got the best apples in the eastern United States.” And he said, the devil said, “I’d like to have some.” And Jack said, “Well, what you’ll have to do, you’ll have to go to the very back part of my farm on the highest hill–you’ll recognize it–in the tallest tree, in the very top limb. That’s where you’ll find the sweetest apples.”

So the devil said, “I think I’ll pick some of ’em.” So he left and started to the apple tree. And Jack followed him with a hatchet. And the devil clumb–that’s one of those terms that we use, even though I’m in education–clumb up the tree, and the devil was in the top limb, set down, and sure enough, he picked apples and it was the sweetest, best apple he’d ever eaten. And, while he was up there partaking of them apples, Jack took his hatchet and he carved a cross on the bottom of the apple tree. And, I don’t know what you know about devils and crosses or not, but the devil couldn’t get by the cross because it was on the tree trunk, so he was stuck up there so long. For like 43 years, he couldn’t get down. And he was up there, and of course he was mad all this time.

Well, Jack eventually died of meanness and old age. And his first stop was heaven, and St. Peter said, “You’re so mean and bad, you can’t stay here.” He said, “You’ll have to go to hell.” And of course, when Jack died, the spell was released, so the devil came out of the tree and he walked back, was walkin’ back to hell, and he was mad and thirsty–he’d been up there for a long time you know, with nothin’ to drink. And he and Jack got to hell about the same time. And they fit–that’s one of those words that we use–they had such an awful fight. The devil was mad and he was ripped, and Jack was ripped because he got kicked out of heaven. And the devil said, “You can’t stay here in hell.” And Jack said, “I got to, I haven’t got any other place to go.” And the devil said, “No, you can’t.”

They fought some more. The devil got the best of Jack. I tell the guys that the devil gets the best of a lot of us, from time to time, you know. And I kind of turn this into a religious service. No, not really. But the devil and Jack–the devil started to get the best of Jack. And Jack took off runnin’. And he lit out runnin’–I use some of this terminology–and when he did, the devil picked up a hot coal out of hell and he flung, flung it at Jack. And it come bouncin’ along, you know, and Jack saw it, and he said, “You know, I’ve been condemned to wander through eternity in darkness now. I can’t go to heaven, I can’t go to hell. I might be able to use that coal.” And he started to reach down and pick it up, to use it for a light, and he realized it was hot. So he looked over, and in a field, sure enough, there was a pumpkin. And he took his pocket knife and he hollowed out the jack-o-lantern, the pumpkin, and he put a hole in it and put the hot coal in there and Halloween night, you can still see him goin’ up Union County and some of the other places with his light.

And that’s how my grandfather told me the Jack-o-Lantern got its name.

Lyndall Toothman

[My family had a wood cookstove.] It had a big oven with two doors that swung both ways. I’ll tell you a little story about that oven. It was a cold, cold day, and Mother had left both oven doors open so the heat could come out, and we had a big ol’ cat there, and the cat crawled up in the oven and went to sleep. Mother got ready to get dinner. Why, she shut both doors and built a fire! [Laughter.]And we heard this cat a-screaming, and we were running around the house but we couldn’t find it. We got out around the house and we came back in and we could still hear that cat a-screaming. All of a sudden, Mother thought, “It must be in the stove.” She opened the stove door and here came my cat. Its paws were scorched and its hair was singed just a little bit, but the cat really wasn’t hurt. But it sure never went back in that stove!

So anyway—we had chicken or turkey. Up until I was twelve years old, I had to kill those chickens with an ax and “whang” on the chopping block! Then I plucked them and all that. After I was twelve years old, I shot them. By then I had me a .22 rifle. It was one of the first bolt actions rifles that was ever put out. A single shot. I ordered it from Sears and Roebuck. It cost $4.98. I remember that very well because I had got five dollars for hoeing corn that summer and I paid for that rifle myself. First evening I got rifle, I got my shells and went over the hill and killed a squirrel. Dad thought that was great.

But that first Christmas I had the rifle, Mother sent me out to kill a chicken. She had some special blue hens that were extra good layers, and then she had these dominickers[CE1] that were a whole lot bigger and better to eat, and they didn’t lay like the blue ones did. She said for me to get her a big hen and “Don’t kill a blue one!” So, I went out and shot that dominicker right in the head, and there was a blue one in line with the shot and it went right through its neck, and I’d killed a blue one and a dominicker both at the same time.

I was really nervous about going in and telling her about shooting her blue hen.Dad was in and I knew I had protection, so I said, “Oh, Mother, I shot one of your blue hens.”

She said, “I thought I told you not to shoot a blue hen.”

I said, “Well, I couldn’t help it. It was right in line with the dominicker. I got the dominicker, but I’ve got a blue hen, too.”

And she said, “Well, I reckon if you killed two birds with one stone, it’s all right.”

Will Seagle

The railroad had paid me one day and I was comin’ home through Otto that night. [Some] robbers jumped from behind a stump, and said, “Hands up!”

I said, “I guess not.”

They said, “Hands up or die!”

I said, “All right now, I see.” It wasn’t too dark. But I run in the creek and got me a rock. I just did miss one of ’em as he went behind a tree. And so, he run back out. Thought they could get me t’run, y’know. They had them old knives—you’ve seed ’em, that you open and they won’t shut till y’mash the spring. I’d bought one of them that day, I happened to have it in my pocket. I grabbed it out, for I thought they was going t’take my little dab of money. I didn’t get much, but I’uz going to keep it. And when one of ’em come back t’me, I made a dive f’him that way, and I stuck it in his shirt collar. And I cut that shirt and his britches, his waist and grained the hide plumb down till I cut his britches braces. He said, “I’m cut!” He ran back and that ended it up.

After that happened, Priest Bradley give me a pistol. He said, “You can carry it and hide it over there and not carry it on to work.”

I come back that night, and somebody’d blacked a tree stump and put a coat on it. Oh, it’uz the awfulest-lookin’ thing. I said, “Now,boys, I hate t’shoot anybody, but I’ll shoot you, just as sure as the dickens. Now I’m goin’ to do her.”

I hollered two’r’three times at ’em, “What’s up?” I walked up a little closer and I said, “Speak to me!”

They wouldn’t speak—[the stump] couldn’t speak! [Will laughs heartily.]

I took that gun out, and it went “Bang, bang!” [The stump] never moved, and I walked up to it and kicked it and hit that dressed-up stump. [The pranksters] were way up on the mountains, behind trees. You never heard such laughing.

Luther Rickman

LR: August the 26th, nineteen hundred and thirty-six, I was gettin’ a haircut in my barbershop. Heard the gunfire. When I heard the gunfire, it was in southerly direction. I ran out the door and as I hit the sidewalk, Sanford Dickson hollered, said, “Sheriff Rickman, run to the bank. The bank’s bein’ robbed. They have just gone out in a black car.” When that happened, I ran into the front of the bank and Mr. T.E. Duckett was comin’ in–

Mrs. Rickman: At the back.

LR: At the back of the bank. And Ms. Druilla Blakely–

Mrs. Rickman: Was the only…

LR: Was the only person in the bank when the robbers came in. When they called for the money, she screamed and ran out at the back of the bank and into the back of Dover and Green’s drugstore. And screamed to Dr. Dover that the bank was bein’ robbed. Dr. Dover walked out at the front door and, as he hit the sidewalk, one of the robbers with a small machine gun said, “Big boy, get back in there!” And shot down at near his feet. Dr. Dover said he felt of himself as if he was bein’ shot. From that, Fred Derrick ran into the bank.

Mrs. Rickman: …but he saw when…

LR: Oh, I’m a’tellin’ ’em what happened. Ran into the bank and said to me, “Sheriff Rickman, we’ll get some guns and ammunition. And ran to Reeves’ [hardware store] and began to jerk down guns and ammunition. And from that, identified two men and jumped in a little old Ford–

Mrs. Rickman: –took off down the road.

LR: And started south in the direction the robbers had went and a man hollered at me, said, “Sheriff Rickman, nails in the road!” And I took the wrong side of the road and dodged the nails and when I did, the nails lasted from Clayton to Tiger, Georgia. A little below Tiger. I went from there to Cornelia, Georgia. And when I got in Cornelia, I got a message that that car had turned on the easement road. I came back and traced that car from the easement road across to the Warwoman road. Went east to Pine Mountain. Turned north and went to Highlands [North Carolina]. And from there, over into Transylvania, North Carolina into a loggin’ camp where these robbers had a hideout. And from there, the robbers spent the night. And next night, had a wreck in Old Fort, North Carolina and wrecked their car and held a man up from Charlotte, North Carolina and took his car. And ran his car a few miles and the car broke down, and I found it on an old mountain road. From that, I went from there to Spruce Pine, North Carolina. And got some information.

This was such a fun podcast! I’m really excited to have found your podcast back in Feb. I anticipate each new one so much. I grew up in southern West Virginia & really miss hearing these voices….the voices of my dad especially. He was such a great story teller & we never thought about recording him.