Appalachia is renowned for its moonshine–that clear, high-proof liquor illegally distilled deep in the woods. Originally, the distilling process came over with Ulster-Scots who settled in the region and adapted their whiskey distilling techniques to a New World grain: corn. For centuries, distilling was a specialized craft, but after the 1950s, manufacturers focused on increasing quantity, which decreased the quality of the product. In Rabun County, moonshiners prided themselves on producing high-quality, small-batch moonshine. The geography of the mountains were naturally secluded and an ideal place to brew liquor. However, revenuers often made their way into the region, and busted stills! In this episode, we’re taking a look at how moonshine is made, and the experiences of both moonshiners and lawmen in Appalachia. Join hosts Kami Ahrens and TJ Smith, along with special guest Barry Stiles, as we talk all things moonshine and listen to excerpts from Conway Watkins, Lamon Queen, Leona Carver, and Simmie Free. Learn more about moonshine in The Foxfire Book!

Copper moonshine still.

Transcripts:

Conway Watkins

CW: That old federal man talking to us there–me and Buck [Carver] kept a clean place. We made good whiskey. And we kept it clean around there; everything cleaned up. That old federal man said, he said, “Boys, I hate to cut a place like this down.” He said, “This is clean. I’ve seen kitchens that’s not as clean as this place is.” I said, “Well, as far as I’m concerned, sir, you can just leave it.” I thought we would just have a little fun, now that we done got caught.

FF: Well, how many people were there?

CW: There was seven of the lawmen.

FF: Seven?

CW: They had us surrounded good.

FF: Seven?

CW: Seven. And then Lamon and Payne come down from the Georgia side, and they made nine. I never did feel bad about making liquor to feed my children. There wasn’t no jobs.

FF: No, well this is what people…

CW: I still don’t feel a bit bad about it.

FF: Not when it’s poison liquor.

CW: ‘Course, I don’t want to go back now. I can live rather well, but back then, why there wasn’t no money in Rabun County but for making whiskey.

FF: I know it.

CW: We was a’taking some of that whiskey down in North Carolina and sellin’ it. Some bootleggers down there next to Franklin. There was an old one-eyed man, lived on the right-hand side of the road there. I can’t think what his name was. But he’d take about two cases a week and we’d take it to him. And–I would–I went down there one night and carried six cases, and he was gettin’ two of ‘em, and there was four more around there gettin’ a case a piece on the other end. Bootleggers down there, you know. That old man on the bank there, that old one-eyed man said to me, said, “You better get out of here. You better get back to Georgia.” He said, “This law done found out and said they is goin’ to catch them fellers that’s bringin’ that liquor in here from Georiga. And said they’s goin’ to pick us bootleggers up, just like a duck a’pickin’ up corn.”

FF: So, you just took back the other four cases?

CW: Yeah, I just left and come back. Once I got his money for his two cases, I got back across the line.

FF: Well now, they were called bootleggers because they were sellin’ it?

CW: Right, they were selling it.

FF: You weren’t called a bootlegger for makin’ it; what’d they call you for makin’ it?

CW: Manufacturing.

FF: Manufacturin’, huh?

CW: Mhm. But I know, there was one police ? that lived up there on ? Mountain that we were selling two cases of liquor to a week, for eighteen dollars a day. That’s what we was gettin’ for it.

FF: What’s in a case, four gallons?

CW: Six.

FF: Six gallons?

CW: Yeah. We was gettin’ eighteen dollars a case. And we was sellin’ him two cases. And he was takin’ it to Highlands and bootleggin’ it out. Pintin’ it out to people, you know. And they thought he was makin’ it down there and had a little place of his own, and they was huntin’ for him when they found me and Buck.

FF: But you were the ones that’d been supplyin’ him anyway?

CW: Yeah.

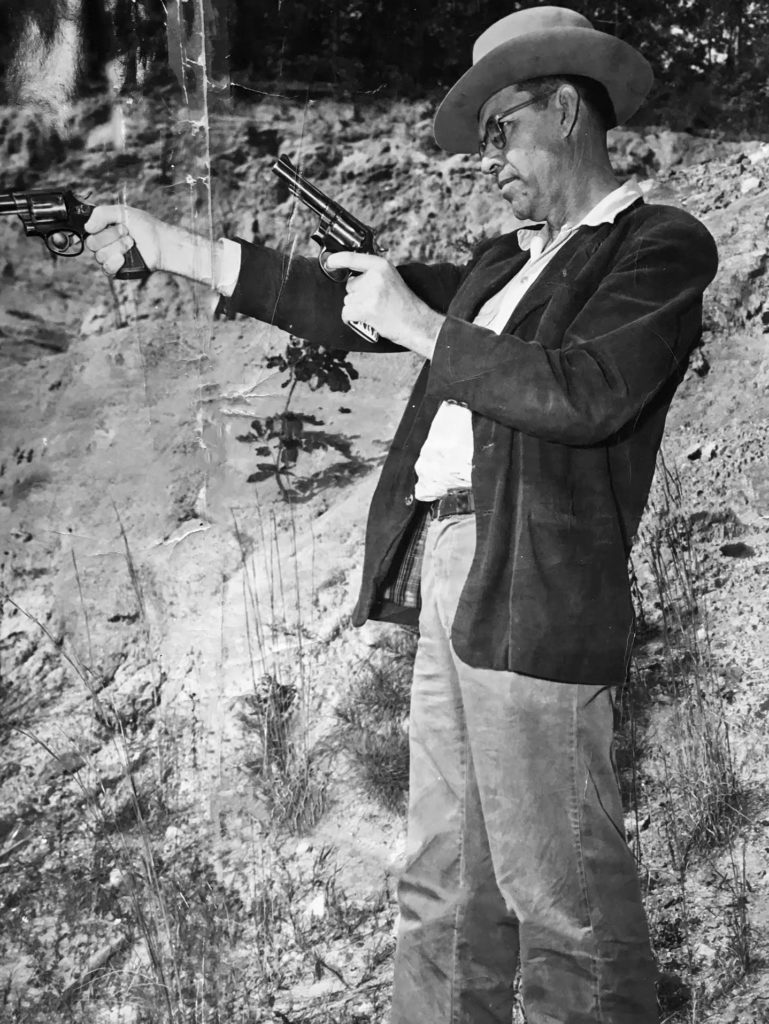

Sheriff Lamon Queen. Image courtesy PJ Riner.

Lamon Queen

FF: Well, would you tell us about when you were sheriff?

LQ: Well, when I was sheriff, it was just two of us then. We wasn’t on salary; we was on fee basis. You know, if we didn’t make any arrests or do anything, we didn’t get paid. Had to furnish my own car, pay my own deputy. And there was a lot of moonshinin’ goin’ on then. We’d have to get out of a night with the federal and state law and raid moonshine stills. We had a lot of races out of liquor cars. And we’d sell ‘em–we’d get a certain percent out of ‘em when they was going to the lot to be sold. And that would help pay our … we’d get so much for cuttin’ a moonshinin’ still. I believe the county paid that, it was $10. I’ve cut as high as twenty in one month. That’s when people wasn’t–there wasn’t no industries in here much, you know, and people had to make a living. Well when shirt factory and Rabun Mills and the rest of them come in here, why people could get a job. And the biggest part of them just quit that moonshine business and went to work. They’d much rather work than to make whiskey. Beg your pardon?

FF: There weren’t many jobs around in here, were there?

LQ: Oh no, you couldn’t hardly get a job around here at all.

JQ: There wasn’t nothin’ around here but moonshine.

LQ: Well I wasn’t a’foolin’ with moonshine then. Drank a little.

FF: What a way to make a livin’ though.

LQ: Yeah, it was hard when, say, Blalock and myself was in the sheriff’s office, ‘cause we didn’t know what it was to go to bed and sleep all night hardly without havin’ to get up and answer the call.

FF: For what now?

LQ: Well, just different things. Sometimes other laws from other counties would come in with a warrant, you know, want us to go and help ‘em locate whoever it was they had the warrant for. And sometimes the laws come in with a report on a moonshine still somewhere and wanted to know exactly where to go and they’d come to say and get me up.

FF: That took place a lot of times at night?

LQ: That’s right, a lot of times. And then, a lot of times at night we was set out all night, waitin’ for the whiskey car to come through. We’d have a good race, we’d catch it. Get a little profit out of that.

JQ: I saw one go through one morning. I was fixin’ to get some bacon or eggs or something for breakfast, and i just grabbed a ?ful and took off over there and as I come back, why here come this car through, boy he was packed onto the top of that car. I went and told Lamon and they caught him.

FF: Well how did you know that? Did you see the–

JQ: You could see it. You could see the boxes of cans.

LQ: Fruit jars.

JQ: Fruit jars.

LQ: Five-gallon fruit jars, they usually had it in. And you could always tell the way one rides; bounce, if they’re loaded heavy, why, sort of like a wagon. It would spring up and down, it’d just bounce. You only had to look at one to tell if it was loaded heavy or not.

FF: So when you saw that, you’d stop ‘em and search the car? And then what happened? Did you get to keep the car?

LQ: We’d take the car and have to get the block number off it and all, and turn it into the clerk’s office, and he’d fix the papers out. In about 40 days it’d sell at auction. Highest bidder would buy it.

FF: And what’d you do with the whiskey?

LQ: Pour it out.

FF: Well, did they, ever buy back the car?

LQ: Sometimes they did. If we were to catch them with it, why they’d buy it. Sometimes, what we’d call a bush bond. If they took a bush bond, we didn’t catch them, why they’s afraid to come back and try to buy it back. They’d get away, you know.

FF: A bush bond?

LQ: Yeah. That’s when they jump out and run, you know, you can’t catch ‘em.

FF: Right. Were there big operations up in here or was it, like, small?

LQ: Well, it was a lot bigger than you have now. Sometimes I have, now i don’t know whether you know what I’m talkin’ about or not, but these boxes that they ferment this mash in, well some of the boxes would hold about 500 gallons of mash. And we have cut one or two with 25 boxes. That’d be a lot of mash. I don’t know how much whiskey they’d make; several hundred gallons though.

FF: Was anybody ever after you because of that, you know? I mean, did you feel like your life was in danger?

LQ: I never did feel like i was. For these people, they was just tryin’ to make a livin’; they weren’t out to hurt officers. They’d get away if they could. But they wouldn’t resist and try to hurt officers. The only time I ever had anybody try to hurt me was, I was after a truckload of whiskey. A fella from Virginia. And he backed over my car and tore it up, like to have gotten me. And i finally caught him later though. He unloaded the whiskey. I could get help from a liquor man about as good as from soemboyd that’s a church man.

FF: Yeah, because the just felt like they were earnin’ a livin’, is that?

LQ: That’s right. They didn’t mean any harm by making whiskey. They was just tryin’ to feed their family. I’ll tell you a little story that happened on Persimmon. Old man over here had two boys and they’s making whiskey, and at night at supper he told ‘em, said, “Now I’ll tell you boys, I thought you’s all blockadin’ out there. I went up there today and found your still and I’m gonna tell you somethin’. The first time I catch you working on a Sunday, I’m goin’ to report you.” He didn’t mind them making whiskey but he didn’t want them breaking the Sabbath and working on a Sunday. None of ‘em hardly would drink. They just made it to sell. They said they didn’t make it to drink.

FF: Would they make it differnet if they made it for themselves?

LQ: Well they used to make good whiskey in this county. And then there was a bunch come in here from another county and got to brewin’ what they called stack steamers? And groundhogs and one thing or another, you know, how to make it fast. And it was rough. And that just raped the sale of whiskey nearly in Rabun County.

Leona Carver

FF: Well, when you was makin’ the stills where’d you all do it, did you just do it in the backyard, or did y’all have a shed where you did it or?

LC: We did it in the house.

FF: Oh you did? Oh.

LC: Mostly was in the kitchen.

FF: Could y’all have gotten caught any time?

LC: Yeah, sure could’ve. It was a risk we took to make ‘em.

FF: Was it common for women to help their husbands back then?

LC: I reckon I was the only woman that did. I never did hear anybody else say they did–they may have.

FF: Well, while you was doin’ this, did you have a job? Or did you just do this all the time?

LC: No, most of the time I had a job and we’d do it at night, in the evenin’ after I’d get in from work.

FF: When you built ‘em, what was–I know you had to have copper, what other stuff did you have to have to build ‘em?

LC: You had to have the brads and the cuffs for the brads. Then your tools–you had to have a rubber hammer and another hammer, then, to brad with. We’d tin-lock it, and he’d beat ‘em down with that hammer. And i’d hold ‘em while he was a beatin’ ‘em to tin lock ‘em. Then we’d put the brads in.

FF: And you say you was inside of the stil when you did this?

LC: Mhm. The beatin’s, I was. When he was puttin’ the brads in.

FF: While you all was doin’ this, what did he do? Did he have a job or?

LC: No he didn’t.

FF: He just, he did that all the time?

LC: No, he made stills and then he made liquor too.

FF: Did he make it in the backyard or did he–

LC: No. In the woods.

FF: Did you know?

LC: No, I never did know where his place was.

FF: You’d come home after work and start makin’ ‘em?

LC: Mhm. He would have ‘em cut out and ready to fix, and I’d come home in the evenin’ then, and help him with what we could do that night.

FF: Well was it hard on you to do that? And raise 11 kids too?

LC: Yes it was. I’d go to work and work 8 hours, then come home, fix some supper, then we’d work on the stills.

FF: Why did you do it if it was such, did he make you do it?

LC: Well, he’d ask me to. He tried two or three ? to help him one time, but it made so many dents in it, it wouldn’t last anymore. So he’d wait ‘til I got off work and help.

FF: So you was pretty good at it, huh?

LC: Yeah, pretty good.

FF: I guess it wore you out a lot to work on it and then to have to fix dinner and stuff like that, didn’t it?

LC: Yes, it sure did. I’d come home from work and I’d feel like goin’ to bed, but I’d stay up and help him ‘cause he wanted me to.

FF: How late would you all stay up?

LC: Maybe twelve, or one or two o’clock.

FF: Did makin’ the stills, did it help put food on your table?

LC: Well i guess it did sometimes.

Simmie Free

Simmie Free

SF: Well everybody knows you have to cook them one day and let it stay ‘til the next day if you do it right. That was the only way we was fixin’ to make liquor. Just doin’ it right. And let it work some, let it work clean–some say fifteen days and some say twenty days. Don’t count the days; take it under the weather and taste your beer. When your beer gets ready to run, it’s got a bit of whang. When it goes to gettin’ a bit of whang, you better be makin’ your liquor. That’s the truth. I don’t have to have water. I been here so many times and made so much liquor, i don’t need no water to temper liquor with. I can give it here. Look at it then know what it is. You wouldn’t know it.

FF: Right.

SF: You might think it’s buttermilk, but it wouldn’t be. I’ll tell you one thing, there’s a lot of people who don’t know how to proof liquor.

FF: Yeah.

My father learnt me a way back yonder when i was a young girl. Back when I was nine year old.

SF: Some say they leave it a hundred proof, some says more ‘n all like that. There ain’t nothin’ but that thing to do. When you run your liquor, if you know how to make it like i do, let it run. And when it breaks, i can stand 30 feet from where the liquor is comin’ out, and I’d say, “Well, she broke.” I could tell it that quick by looks. And i made as good liquor as any man ever made in Habersham County, Rabun County, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia–anywhere else. I been a liquor-maker. But I never did make none to sell. Always only barely made enough to do me. But I got by with it.

FF: But you did sell some eventually, didn’t you? You sold some and paid for your land and all, didn’t you?

SF: If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have a home. I had to. I told my wife, I’d go to the chain-gang and stay for now on, and I would, and I meant it, ‘til I had me a home. In my eyes, as long as I had it, nobody couldn’t tell me nothin’. I’d done as I said do. I don’t listen to nobody. Not today, tomorrow–your’n or nobody else…if you believed I would, ask the judge would I listen. He’ll say no. Judge’ll say no, he won’t listen. I’m just what I am.

FF: Well, how’d you pay for the land and the lumber and all that? How did you pay off all those debts, for land and lumber and all of the debts that you built up?

SF: Makin’ liquor and damn good management. Even if I did drink. Good management. If it wasn’t for that, never could’ve paid the debt.

FF: You’ve been caught a couple times though, haven’t you?

SF: Caught?

FF: Yeah

SF: Hell, I’ve served four sentences right down here in Gainesville jail for manufacturing liquor. I served two, I kept on–I didn’t go, I didn’t go, they carried me. They carried me to the penitentiary. Reidsville? I didn’t go. They carried me. I didn’t just walk out plumb down there to get to Reidsville. I went down there and stayed two months, and every one of the wardens and all the boss men and things just thought the world of me. I’d be damned if they wasn’t plumb good to me. And two months and fifteen days I was right back here in that yard. Shoot, I been lucky. I ain’t never been unlucky. I been lucky.

FF: Was that the first time they caught you, you went to Reidsville? Or?

SF: Shoot no. Lord, God, I couldn’t have…I’ve been caught six or seven times before they would have a trial. They had warrants; they couldn’t catch me. Hell no. There wasn’t no man on two feet that could catch me.

SF: That fellow over here, he didn’t love liquor as good as I did, but let me tell you one thing right now, he loved liquor good. He did. He would steal it from me and I told him … and then he went and reported me. I don’t like a reporter. I tell the world that and he found it out. He found it out the next thing.