Excerpt from survey of Rabun County schools

Annie Perry

FF: How about you, as a little girl, did you have chores to do?

AP: Yes, I had to feed the chickens and I had to feed the ducks, and the hogs, and the sheep.

FF: Oh, that kept you pretty busy then.

AP: I went to school every minute they had school. My daddy never kept us out a minute from going to school, no matter how much work he had to do that we could help him do it. He sent us to school and find somebody else to help him work, because he valued education. He said didn’t want us to grow up like he did.

FF: Yeah. How many years did you go to school?

AP: Huh?

FF: How many years did you go to school?

AP: How many years did I go to school?

Man: She went ‘til she was 21.

AP: You’ll be surprised, I went ‘til I was 22 years old.

Man: You went barefoot, didn’t ya?

AP: Yes I did go barefoot to school. Everybody else did.

FF: I guess shoes were really important, you didn’t wear them unless you had to, did ya?

AP: No. They didn’t want to wear ‘em, they all wanted to go barefooted.

FF: How many months out of the year did you go to school?

AP: Well, my first school was four months of the year. And then–I went that way for I don’t know how many years, I don’t remember–then it got to be five, then six. And six months is the longest we ever went to school.

FF: Did you get out for summer to help your parents?

AP: We got out in the summer and pulled fodder and cut tops and picked peas. Worked for three weeks during that summer season. But I went to school ‘til I was 22 years old, and I don’t–I ain’t got but seven now, had eight–and of all the eight nieces, finished high school, and they wasn’t extra smart, but they were reasonable smart. And you know, they don’t know as much as I do in some fields. They don’t know arithmetic–not near as much as I do. They don’t know English, they don’t know spelling. Well, I tell you right now, you need arithmetic in your life. And you need spelling. Arithmetic, spelling, and reading is the most essential subjects there are.

FF: The three R’s.

AP: Yes. The three R’s is the most important study there are.

FF: Yeah. I have to agree.

AP: I put it this way, if they had $200 to lend to somebody on interest for two years and six months, they couldn’t tell me, they couldn’t put it down on paper and tell me how much the man or the woman or whoever borrowed the money would be due them at the end of the two years and six months. And if I had this building, this room full of shell corn, I can figure up and tell you how many bushels of corn I have.

FF: How many square feet to a bushel?

AP: 231. Two-hundred and thirty-one square–now they don’t teach them that in school. I don’t–they didn’t teach my young’uns that; I don’t know whether they do now or not. That’s what I call everyday livin’.

FF: Yeah, I have to agree.

A-74-35 Lola Cannon

LC: The first that I remember going to school, we only had five months of school. We were out early in the fall, you know. Later on, we got to have a seven-month school. And I don’t believe–yes, I went to school maybe a couple of years after we had nine-month school.

FF: How did you–to what grade?

LC: I finished what would’ve been the seventh grade. Schools weren’t graded when I went. They was just gettin’ graded; they started the grading process the last, I guess ,the last year I went to school. And then, when you finished the seventh grade, if you had applied yourself right well, you had a pretty good basic learning.

FF: That wasn’t as high as you could go then?

LC: That was until, them country schools, if they rated a certain attendance they had more. And then there was–I’ll tell you where you can get some good information on things like that, if it’s available. I lent my copy of it. There was a little pamphlet put out, about 19 and 12, with pictures of every one of the little country schools, and the teachers that was teachin’ then. And some of them only had 18 students.

FF: And that was a lot?

LC: Uh-huh. That would be third-grade schools. Schools were rated as first, second, and third. Well, those finishing seventh grade could get a third-grade school if they wanted to teach. Now this pamphlet should be, a copy of it should be in the superintendent’s office. I believe that Martin Chastain was the superintendent then. And he visited all these little country schools, riding a mule. And we were always so happy when Mr. Chastain comes. He was a jolly fellow and he was always, always brought some fresh jokes and anecdotes to tell us. He was a loveable person. And I think he was superintendent that year. You might want to inquire in the superintendent’s office. I imagine that a copy was kept of it. I had a copy and several people lately wanted to read, and some way it got lost on the route; it didn’t get back to me. I treasured it a lot, too. One of the things about the little country school that I like so much was in the autumn–late autumn–sometimes the, our seventh grade school–the years we had the seventh grade school–the school closed about Thanksgiving, I think. I think that’s right. Anyway, we would plan a great entertainment for the day. By-laws and recitations and songs and oh, so many things. If the schoolhouse was small–well, I believe they always had the entertainment outside anyway–we’d build a stage just outside the door. And cut evergreens and decorate that space. It was beautiful, we thought. How much fun we had. The parents were entertained. And practicing, and dialogue–it was good for the children. And most all of them enjoyed it.

(You can check out the survey that Lola mentions here!)

Billy Long

FF: Let’s see, you went to school over here, didn’t you?

BL: Yeah. That’s where I got my education, right over there on that little hill. They consolidated this school, just Otto, and there was nobody here but me–and her–with my daddy, and he was gettin’ pretty old. I had to miss a lot, you know, and everything still trying to farm. And I just couldn’t go, I never finished the seventh grade.

FF: How far did this school up here go?

BL: ‘Til the seventh grade.

FF: Do you know why they called it the Last Chance School?

BL: No, I never did. Far back as anyone knows.

FF: You remember any stories that happened to you while you was going to school up there? Did you ever get into with a teacher?

BL: Oh, a few times I guess. No, I never did have no trouble much. I remember one time we had a free brawl over there.

FF: Yeah?

BL: I don’t know if they was tryin’ to raise trouble with the teachers and all, they never would send their children to school unless they just had to. So my daddy went to Franklin that day, or went somewhere, my brother, he was cuttin’ top and throwin’ fodder in that field right in there above the road right here. So they come in to school that mornin’–did you ever hear of the duck shot Loves?

FF: Yeah

BL: Them and Williams and Nortons–Jay Norton–Carl Love, Charlie, and a bunch of them. They was great big boys, a lot bigger than me; I was just a little fella. They start–Margie Pitts, you ever hear of her? Margie Norton she used to be?

FF: I’ve heerd of her.

BL: Harley Pitts’s wife?

FF: Oh yeah.

BL: She was teachin’ school over there. And she put/pulled one of the others the day before for beatin’ each other or somethin’ like that. But the next morning, just at the school, took a–we was sittin’ by a little woodstove writing, we all sittin’ around the stove gettin’ lessons. So we was all sittin’ round there, first thing we know, them … to one another. They come in and jumped on Ms. Norton. I don’t remember how it started. I can’t tell you the details. Anyway, they just made a dive for it. And they got her down. They was ‘bout put her hair alight. And Hobe was sittin’ there–and Carl Love and Buck–all sittin’ round the stove. And he jumped up, or started to, gettin’ to help ‘em, you know. When he done that, ol’ Carl Love reached the stove–you know what I’m talkin’ about–little eye of the stove, there was a stick in one of the stove eyes out. And he reached and got that stovewood from there and cracked Hobe over the head. It cracked that stovewood in two, over his head.

FF: Did y’all have a church up in here anywhere?

BL: Over there, at the schoolhouse.

FF: At the schoolhouse? Is that where you used to go to church?

BL: I went to church up–oh, I guess I was ten or twelve years old.

FF: And this is when they were having school in there too?

BL: Yeah. But now, we quit going to church over there, I believe, before they had, before they built a schoolhouse. I believe I’m right on that. I could be wrong, but I believe I’m not. We quit having church over there then.

FF: When they consolidated schools down here, the children at this school went to Otto?

BL: Went to Otto, you see.

FF: Yeah. Right.

Richard Norton

FF: Do you remember when they consolidated the schools up here? Didn’t they send the school up here in Georgia to Dillard and this one out here, they sent the kids to Otto? Isn’t that how they did it?

RN: Yeah. Yeah they sent, well my kids went to Otto, ? and Kenneth did. They went some, but not long because–I think they went maybe two years down there then they changed them back to Dillard. I think they’re doing the wrong thing now, tearing up that Dillard school.

FF: Yeah, what’s your opinion of them taking the high school kids all the way down there?

RN: I don’t think it’s a good idea, they’re puttin’ too many together. The teacher’s gonna have too many kids. The more kids the teacher has, the less that she can do for ‘em. I mean, you know, I think leavin’ that school down here in Dillard would be the best thing they could do. A lot of the kids from up here finished at Rabun Gap, went to school over here.

Stella Burrell

FF: There’s the Last Chance School up in North Carolina and then the one up by the church?

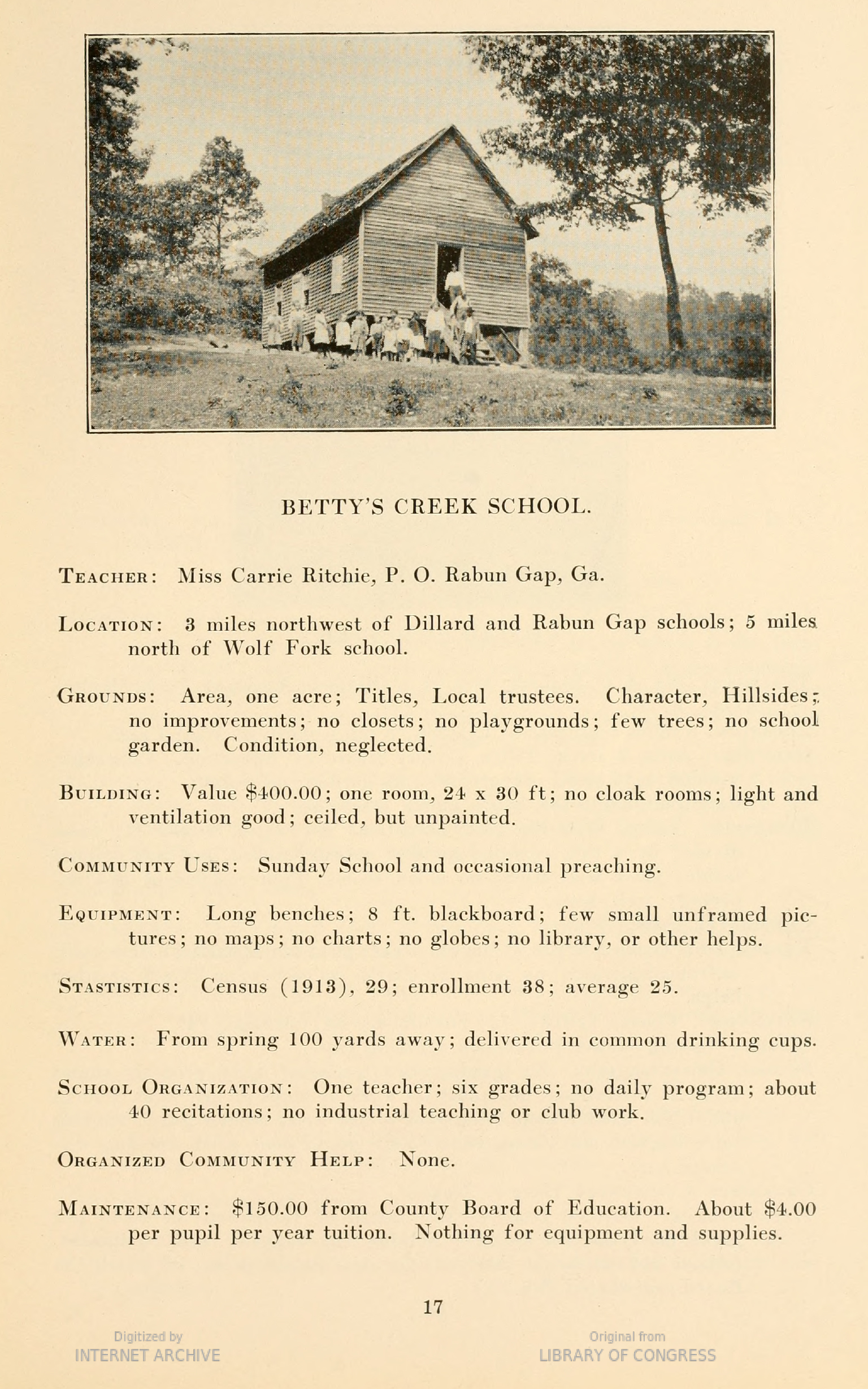

SB: Well, I remember the Last Chance building. I’ve been to it. But I never–at that time, I don’t remember ever going to a school there, because I always went to the Betty’s Creek school. And I remember it quite well. I went two years.

FF: Can you describe it?

SB: Yes, I have some pictures of the old building, as they were building the new church and moved it over.

FF: Didn’t you all like help tear it down?

SB: Yes, Ned and I tore that old building down. And daddy. It was used, it was really, it was donated as a church–I mean school, and the people used it for church purposes.

FF: That was up until the church that’s there now was built?

SB: Yes. And I only went two years, now, to the school ‘til we were consolidated with Dillard.

FF: How many classes did they have there?

SB: We had seven classes.

FF: Seventh grade?

SB: Uh-huh, and we had go then to Rabun Gap to high school, or Daisy–at that time I was in grammar school and she was going into high school, and she went to Tallulah Falls. But I went to the third and fourth grade there. Quite a little different.

FF: Do you remember anything in particular that comes to your mind about that school? The teachers or any experiences that you had?

SB: Well, Daisy Ramey was the first teacher that I had there. And she was very young and very active. And she would get out and play with us and turn cart wheels and all things like that that you just wouldn’t expect from an adult, but she did all those things that it’s something you remember, very much. And she would play ball with us, and just anything that children played, she played too. And then Ms. Meg Grist, she was an elderly lady, well she wasn’t really at that time I suppose, but she seemed to be to me. And she gave prizes more than most teachers did for things she would have you to do work. They work up so much material in a geography book or on a certain subject and she would give a prize for it. They were both really good teachers. They had so many to, you know, different classes, that you know, you studied while somebody else was having–so if you were having, you had your arithmetic, she went on through with the arithmetic part to the seventh grade, then she’d go over the english, and all that from there. And you could draw or study or something during that time, while she was teaching the others.

FF: Do you remember how you felt when you started having to go to Dillard instead of Betty’s Creek? Did you have any feelings about it or did you miss the old school?

SB: Well, I don’t suppose, I was really too young to think about it, but I do think the adults felt like that when you took a school out of a community, you took something from it. Because I don’t think they ever were as active in the big school as they were in the small school. Yet, I’m sure they realized that, you know, you probably would get a better education by combining, but still they didn’t take us–they didn’t go to all the plays and all those things that you had. Because, for one reason, transportation at that time, it was hard to go. It was five miles from Dillard, and we were used to walking back and forth the two miles to school. But we had to go and we thought we had too much of that. Because we did that during revival, if we’re going to church at night, or whatever. And the parents went to all the social events, so. And they had box suppers and things like that to raise funds for the school. And so when they went to the community school, I can’t remember my parents ever going to anything that they had the Dillard Community School.

FF: When you switched over, did you ride a bus then to school?

SB: Yes we did.

FF: The buses then came up as far as you lived?

SB: No. It only came the main road and everybody had to walk out. It didn’t make the little roads like it does now. You had to walk to the bus.

Arie Meaders

FF: Well, do you remember much about school?

AM: Yeah, I remember going through that school up there and the teachers we had.

FF: You said it was a five-month school?

AM: A five-month school.

FF: Was that in the wintertime?

AM: Well, it would start in July, I think we had two months in the summertime maybe. Then the next three months, from September, October, and November. It was usually out around Thanksgiving week.

FF: And, so you’d have a break in there for crops?

AM: We had to stop and pull our fodder, you know, everybody pulled fodder. I don’t know what they done it for. There wasn’t much to it.

FF: Well, with your schoolin’ then, did you go through the equivalent of say, the sixth grade or somethin’ like that?

AM: Well, I’d say the seventh grade, because we come here and I took the seventh grade at that school over there two years. And I thought surely I got through the seventh grade.

FF: And was that as high as it went?

AM: That’s as high as it went. And if you went to school more, you had to get a way to go to Cleveland; they had a high school up there that hadn’t been, they hadn’t had a high school long. And a lot of people would walk and go–that is the boys, you know. The girls didn’t or they might go and find a boardin’ place and board up there and go to school. And quick as you got through high school, they’d go to teachin’. And a lot of them went to teachin’ after they got through the country school over there. Little country school that we went to.

FF: Do you remember at school and at home and around, just havin’ games and toys and recreations? Free time? Recess at school for example, what would you all do?

AM: Oh we usually build playhouses out in the woods in the fall of the year, in October when the leaves is pretty, you know. String leaves together and go around and leave a door and a window, take rocks and get moss and put that on for the chairs.

FF: Yeah.

AM: Oh, we had a good time. They gave us plenty of time to play. We had mornin’ recess and dinner recess was an hour. And fifteen or thirty minutes in the mornin’.

FF: Was the school in a church building, or it was a regular schoolhouse?

AM: No, it was–the church and the school was built on the same grounds.

FF: But they were two different buildings?

AM: Yeah. At first it was just one room, and then they enlarged that one room as population began to increase, you know.

FF: Was that school on Cartoogechaye?

AM: No it was at Union Church.

FF: Oh yeah, okay.

AM: The name of the church–it was a Methodist church, but they named it Union Church. And it was for everybody, you know, not just the Methodists.

FF: Right.

AM: And the schoolhouse was down below it a little bit. And then they built another L onto it on the back of it. Onto the end of the old one, and then they extended it for another room for the first graders and second graders. They had up to the fourth grade–up to the third grade in that room. And then if you took up to the fourth, you went to the other room.

FF: So they had two teachers.

AM: They had two teachers. Oh they was a crowd of them at the school. ‘Bout all they could do, you know, great big grown boys would come to school, get to play ball.

FF: What did you like in school, about subjects and stuff? Did you enjoy any?

AM: I didn’t have any trouble with any of them.

FF: You went right through English and math and everything?

AM: Yeah. Yeah it was always easy for me. There was one that couldn’t learn nothin’, and she’d sit down and copy what I had on my tablet and she’d hand hers in. If I was wrong, she was wrong too, you see?