In honor of Black History Month, this February we are releasing a special four-part series that highlights African American experiences in Southern Appalachia. Our fourth week features excerpts from an interview conducted in 1976 with Anna Tutt of Cornelia, Georgia. Anna was born in 1911, and shares some of the harsher realities of growing up in the Jim Crow South. To read the rest of Anna’s story, pick up a copy of Foxfire 8.

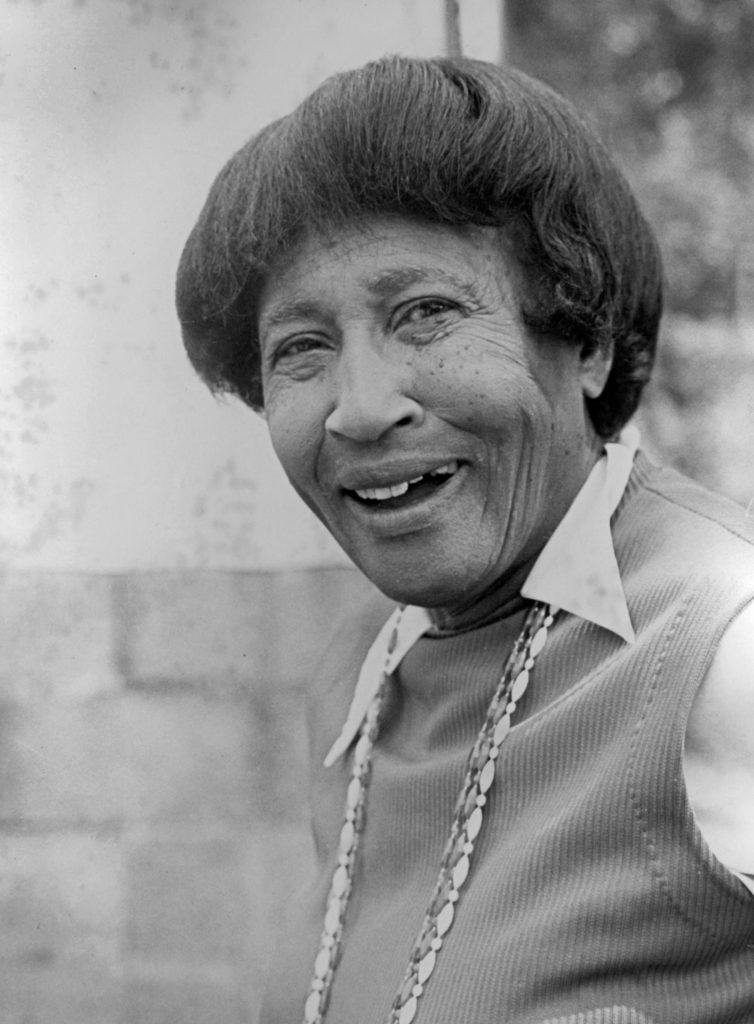

Anna Tutt, 1976.

Anna Tutt Transcripts

FF: Do you think families used to be closer?

AT: Sure, sure. They used to have prayer, blessings at the big table, and things like that.

FF: Were the grandparents and maybe other, older single members of the family included in this? You know how now, you got grandma and granddad off in the nursing home, that kind of stuff?

AT: Yeah, yeah.

FF: Do you feel like families are not so close as they used to be.

AT: No, no. And what have separated lots of the families, I think these mills and plants and jobs and stuff like that—the father, he comes in. The mother’s goin’ out and the children are left alone. Some of them practically rear themselves and don’t know what to do. And children need their parents. We used to when we lived in the country—which is different from now—we come in from school ‘bout this time or maybe later, and my mother was always there in the rocking chair by a big open fire or something. And if it was in the winter time, our father was out huntin’ or something like that, or cuttin’ wood. And they’d always have something cooked up. We’d go to the stove and look in the warmer and get something to eat, and we’d go out and play a while and then we’d do our chores. Bringin’ in chips or goin’ to the spring or branch to get water for the night and totin’ in woods and stuff like that. But now, the children comin’ home, mama’s nowhere to be seen. And why, because they’re on the job. I said that wants—the material things of the world I think is what got it. That’s why the children are like they are, I believe. We automatically just come in lookin’ for our grandmother to be there when we got home, or our parents. If we didn’t find them at home, we wonder what was the matter. We’d go huntin’ for ‘em. But I think the plants and things is what…and then people don’t make the children go to school or to church or to Sunday School like the used. Like I said, we used to automatically—we grew up, and it just came natural for us to get up and know when Sunday mornin’ come, to get up, Sunday clothes, goin’ to church and Sunday school. But now sometimes, I go to Sunday School, the road is just full of little children playin’ ball, stuff like that, see? Well if you don’t train ‘em now when they’re little, which way are they goin’ to go later on? I blame the parents for that. They could send them—and then if they got up grown and want to change, that would be their business.

FF: Did your brother get to finish high school?

AT: Yes, through junior high.

FF: And what does he do now?

AT: He works at the Reeves Hardware. He’s been there about thirty-somethin’ years.

FF: Really? Gosh.

AT: Yeah we all finished high school. My sister up there finished high school. And he did too. And I did.

FF: Was that customary for most of the people up here?

AT: Yes, up here it was. But in the country it wasn’t. Fourth grade, or something like that you know. Because we had to stop out and knock corn stalks, cotton stalks, clean up new ground, burn briars, and stuff like that. Start ‘long in February—later part of February or March, somewhere like that. And then some part of December we’d go to school. And if there was scrap cotton to pick or something like that, we had to help get that out. So we didn’t get much schoolin’ in there.

FF: But up here, did you all go the same way as the white children, and y’all went about eight or nine months a year?

AT: That’s right. Sure. But that was just the way people lived then. That was just the way they lived.

AT: I can recall one time, I know, or once or twice. We children would wake up and hear my father walking in the house, in the dark. And we said, “Pa”—we called him pa—“Pa, what’s the matter?” And he said, “They are hangin’ so-and-so-and-so-and-so over there.” I can’t recall the name. And it was about, I guess, a mile maybe, across a creek over there, it was a—seems like the tree was a white-lookin’ oak tree. And I think they say a hangin’ tree never has any leaves on it or somethin’, it’s just dead-like tree you know. And they’re hangin’ so-and-so.

FF: Did they leave the rope up all the time?

AT: No, no. We children never did see anything. I don’t know whether our father kept it from us or what. And he said—

FF: What were they hangin’ him for?

AT: Well, I don’t know.

FF: Was it legal?

AT: I don’t know about that. I was small, see? And he would say like this, “Y’all be quiet, because if they come and ask Pa to help take him down, I will have to go.” And naturally, we were frightened. But that’s all that was said.

FF: (cut off) …to cook for you?

AT: Well, in wintertime, collard greens, baked sweet potato, sweet potato pie. She usually had two big hogs out in the pen, big as elephants almost! And ‘long ‘bout this time of year, fresh meat. And cornbread. She had a cow—buttermilk and butter. She had chickens on the yard, and she’d always put the chickens up by the house, two or three days or more and feed them. She’d make the feed up with meal and water, make it stiff like that you know? And feed ‘em buttermilk and the chicken taste more like chicken than it do now. Only way you know you’re eating chicken now is it says “chicken.” But it had a flavor to it. Now she would just go to the yard and get ‘em, like that, she’d put ‘em up. Fry ‘em and she knew how to curl out the hens, you know, if they’s in the layin’ stage. She’d make dumplin’s out of them or somethin’ like that. And we had plenty to eat. Wasn’t nice, but we had plenty. Peas, collards. In the spring of the year, cabbage, beets, corn, squash, tomatoes, onions.

FF: Did you all can much?

AT: Yes, oh she loved to can. She’d take the apple peelings and make jelly out of them, and she’d take the apples and make, uh, apple butter or preserves. Now that’s good, apple preserves. Pears—anything, she was a thrifty, I say a conservative, or a—I don’t know how to place it, but she wasn’t an extravagant person, you know.

AT: I wish you had known her. To me, she was just beautiful.

AT: Now, instead of roamin’ the streets, house to house or somethin’, she always had a little basket. They don’t make ‘em like that now, they was strong basket with a little handle to ‘em. But they were weaved like these big cotton baskets and things. And she had that with quilt scraps or her crochetin’ or knitting. No, not her knitting, her crocheting. Yeah, crocheting stuff. Quilt scraps and scissors and thread. And she’d be sitting by the—the house was built different from this one. Big fireplace with a beautiful mantle like that. And one in the other bedroom. And the kitchen and dining room went back that way. She’d always sit by the fire, making her quilts or sewin’ on something like that. She made a home for us. Very, very quiet person. And seemed to have foresight. Indians are known for that, you know. And as I told you’s that, she was Mohawk or Blackhawk Indian.

FF: Part Indian or complete?

AT: She was full.

FF: Full-blooded Indian?

AT: Full-blooded Indian. Though there’s different tribes of them, you know, and she was the dark type. Beautiful, wavy black hair.

FF: And she didn’t, now, she was Indian—y’all didn’t have any problems here as far as, you know, we’ve noticed they didn’t like, a lot of people didn’t like the Indians?

AT: Well I said she was full-blooded, so far as I know she was, but she might have been just part. You know, but I do know she had Indian blood in her. ‘Cause she used to tell us about that. And all of her family was real dark with soft, black hair.

FF: Well, did she say where they came from?

AT: No.

FF: But that was your father’s mother?

AT: My father’s mother, that’s right.

AT: I wish I could have lived the kind of life that she did. Now you take me, I go, go, go all the time. She said, “Stay at home sometime, people get tired of seein’ you.” But now she could sit and just contented. ‘Course she had got up and—I knew her when she was a young woman. I guess she was about in her 30s when I first knew her though. I can’t recall exactly. But she never was a get-about person. She always was a home person. She always took interest in us. We lived with our mother when our father left and went to Tennessee and North Carolina and all like that, dodgin’ the draft and whatnot. We just, if we decided we’d go stay with her, we’d go stay with her. She just lived down the road apiece, you know. And we always felt welcome. She always seemed interested in us. Now she used to iron, wash and iron for the boss. They wore those white celliot—cellulite—collars—

FF: Celluloid?

AT: Celluloid collars that they done, you know. And I can recall, she’d have a iron up and have a clean cloth down in front of the fireplace. And have those collars ironed up, just as pretty, and hooked ‘em together. And just have a row of ‘em around that fireplace, dryin’ out, you know. When they used that celluloid starch on ‘em. And she could do ‘em so pretty. But we could go down there and to her home and look in the stove for something to eat. She had old high beds—rollin’ foot, old wooden beds—and if we wanted to stay overnight, it was alright. She was very nice.

FF: Do you feel like she’s the person who’s most influenced your life or anything?

AT: Yes, I think she had lots to do with—my mother was quiet-like. Now, I could talk to my mother, tell her anything and wasn’t ashamed or wasn’t afraid. But my mother was a nervous type of person. Not shaky nervous, but so many times I used to wake up in the night—when I lived with my mother, we lived in Crow (Grove?) Town at that time—and she’d be rockin’ over by the fireplace. And we’d say, “Mama, what’s the matter?” And she’d say, “Mama’s a little bit nervous.” She said, “I’ll be alright. You all children go on back to sleep. I’ll be alright.” Now so far as shaken, she wasn’t nervous like that. She was quiet. And I never heard either one of them use an oath. Never. But I give my grandmother credit for taking us. Not in the skill set, my mother was quiet, but I still say my grandmother had the most influence. My mother didn’t have too much say, she was a quiet type of person. Now she was not mulatto, but she was yellow-skinned. Brown, soft wavy hair. And low in stature, not too fat or anything, just medium height. Very quiet. And was a church-goer. Say for instance, when I was in my teens, they used to have frolics, as they called ‘em, or fish-fries, or suppers at home. And I always wanted to go follow the older crowd. And my mother would say like this “You’re too young, if I was you, I wouldn’t go. That’s a real crowd.” Or something like that. But now my grandmother, said could we go to so-and-so, “Nope, stay at home.” And we stayed. See, that’s just the difference in the two. But now anything I wanted to talk over with my mother—“Mama why’s so-and-so” and she’d just ? down nice and quick. Both of ‘em was good.

AT: And I think the white people are nice to the colored people, and the colored people are nice to them. But most of the blacks work out of Mount Airy in the ? when I first come up here. Now there were a few elderly people, I think, that worked for such as the Volks and the Paynes and Kimses and Peytons. They had those great big houses, you know. Some of ‘em worked in them homes and reared the children for years and years. But I didn’t know too much about that.

AT: But I never can recall any prejudice or meanness or anything like that among the white and colored here, you know. No, we got along alright, seems to me.

AT: And I never was a person to anticipate—pardon me—think of, I don’t care how hard the goin’s was, or what I wanted, or needed and didn’t have, I didn’t think of goin’ out and sellin’ my body or hustlin’, as they called it. All over this other stuff. I just learned to do without. I just wasn’t that type of a person. ‘Cause I’ve had lots of experience in my lifetime searchin’, seekin’ for love that I never got. Because my life was all broken up by the divorce with my father, when I was young, and my mother. And things like that. So I was always out seeking for somebody, I guess I had lots of it to give, and I wanted it back. I got tangled up with one or two boyfriends, and ‘course it was violent, I’ve been beat up—I was beat up by one. He was a beautiful dancer. Swift, light, and he was very popular among the girls. But he was kind of a notoriety type. He was the type that you couldn’t trust. He was sneaky-like. So I got involved with him. Like I said I got involved with this older man, and I wanted marriage and a decent life. And be a good mother and good wife, and a home. Those are the things I always wanted. You know, I wanted to live decent—I didn’t want to live just any kind of way out there. But this older man didn’t seem to want marriage, so I started going with this younger man. And he used to give me his money to keep for him. And so this older man came back when he saw I was getting involved with this younger man. And he came back and tricked me to go to out with him to pick up some passenger—he drove a taxi. And this younger man heard about it, and he disguised himself and waited for me to come back. And when I came back, it was at nighttime, he approached me and said he wanted his money that I had been keepin’ for him. I said alright, I’ll go to the house and get it for him. So I came to the house and gave it to him, and when I handed it to him, he knocked me to the ground. And when he knocked me to the ground, he was beating me in my face, see. Well he was swift and fast so I couldn’t fight back, so I turned over on my back and he hit me on my back and knocked the breath out of me—I felt it when it just left out of me. And so he ran, because I cried—screamin’—so he ran. Well, I got through with him. Terrible. I couldn’t see, I could focus it around without holding it still. Well, then I got involved with another one for a while. And I didn’t care for him too much. I just don’t like dirty, underground stuff. I always look for truth, honesty, and sincerity. I just don’t like it. Well, I didn’t go with this one too much.

As I said, I had a nervous breakdown in the meantime, and then when I came back, I dated one or two other men. But not for a while. But then I got involved with another one, was just about as bad as the one that fought me. But this one didn’t fight me, but he would threaten me all the time—would threaten me, threaten me, threaten me. And he wasn’t honest. He would steal. It was very embarrassin’ to me, because the white people here knew he was my friend, see. And I was working at the telephone company. And he’d go in stores and steal things and the lady—the cashier—she knew me well. She’d say, “So-and-so stole.” And I said, “He didn’t have to steal for me, I make my own living and he doesn’t support me.” And she said, “I know that, but I just thought I’d tell you.” So I kept whispering a little pray—“Lord, move so-and-so.” And looked like the Lord wasn’t answerin’ my prayer, so one morning I got out of bed and got on my knees and said, “Lord, you can move him. I can’t. Will you?” So the Lord moved me and him. I had a nervous breakdown and he went away and I never want to see him anymore. Never. But he was a handsome, good-lookin’ young man. And I never want to see him anymore. He was just too dirty, sneaky, low-down. But I see, I just didn’t go for that. So, I don’t think I’ve been involved seriously with anyone else since then. That was back in the late ‘50s

AT: My psychiatrist said that I was too sensitive. He said, “You lookin’ for perfection and you won’t find it.” I said, “Well, if I’m true, why can’t they be true?” He said, “I don’t know, but you won’t find a perfect man.” I guess I’ll just leave ‘em alone then. But the sincere truth, I like, I think marriage is beautiful. ‘Course you don’t find hardly that now, this ‘true marriage’ anymore. Shoulder-to-shoulder. So many are marryin’, and they got some children separated or somethin’ like that. And I guess all that stem back to my childhood life, see. Thinkin’ of a home bein’ torn up—little children, what do the little children think? There’s momma and there’s daddy, and you in between. You love mommy, you love daddy. So what can you do? If people only knew, how it would affect that little child.

AT: I don’t want to say I look back with hate. Lots of people like to bring up…you know, I don’t want to do that. Because I feel like people were livin’ then as was customary to them. Like, different—I can’t phrase it like I want to—but in different stages of life, or in different ages.