May is perhaps the most beautiful time in North Georgia, rivaled only by the luminous colors of fall. The mountains are exploding with every shade of green and the bright blooms of wildflowers. At the Foxfire Museum, our nature trails are home to dozens of unique species found only in this botanically-rich region. While nowadays we recognize these plants primarily for their aesthetic pleasure, historically many of these native species were important sources of food and medicine.

Dandelion blooming.

Appalachia is one of the most biodiverse regions in North America, and use of plants as medicine dates back to the Cherokee and other groups of Native Americans. Until the mid-20th century, most mountain people did not have access to modern medicine and depended on local flora for treatments. This practice, known as folk medicine, was based on the transmission of healing practices through oral tradition. Nearly everyone had some basic knowledge of plant medicine, but there were some people who were more practiced in herbalism.

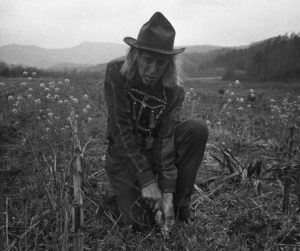

Kenny Runion harvesting ramps.

One well-known mountain herbalist was Henry Cantrell, father to Flora Youngblood. Flora was interviewed several times in 1984-5 by Foxfire students on a variety of topics, many related to folk medicine—skills she inherited from her father. Born in 1865, Henry always told Flora that he spent nearly a decade learning medicine and healing from the Cherokee as a young man. She remembers helping her father prepare treatments as a child:

“I’d have to gather the whole plant, but for some he’d just use roots. We’d trim off the dead leaves and any that wasn’t good and alive. We’d wash ‘em real clean to where there wouldn’t be a bit of grit on ‘em nowhere. Then we’d trim ‘em and fix ‘em. He’d take the leaves and make different things out of them and he’d make other stuff out of the roots. He’d take the roots while they were fresh and beat them up and make little poultices for sores. It’d draw that infection out and the sore’d heal right up.”

Because access to healthcare was so limited—and expensive—in the 1800s and early 1900s, people in the mountains learned to care for themselves or to turn to herbalists like Henry Cantrell. Mimi Dickerson’s mother used to tell her that:

“Y’all run to the doctor too much. Every time anybody gets a little bit sick, they run to the doctor instead of trying to learn something about helping ’em. That’s about what the old folks had to do. The doctors wasn’t so close to ’em that they could call a doctor. They just had to learn kindly to doctor themselves.”

Many families reserved corners of their household gardens for cultivating wild herbs. Esco Pitts’s mother grew rue, comfrey, Jerusalem artichoke, and more. He said,

“All that stuff was in one corner of the garden and it never was plowed up. The rue she made tea [with], and I aint’ seen a stock of rue in many a many days. I just don’t know what she used it for, but I know she used Jerusalem artichoke to make her worm medicine. And the comfrey, she made poultices out of that for swellings.”

These practices slowly died out as what we consider “modern” medicine became more widely available throughout Appalachia, and as carriers of this knowledge passed on. In recent decades, over harvesting and land development have led to the decline of wild herbs. Conservation groups and the government now protect many of these fragile plant species in order to preserve them for future generations. Many plant uses are captured in the Foxfire archives and carried on by a growing community of regional herbalists.

Interior of the Phillips Cabin at Foxfire, an herbalism workshop space.

Join us at the Foxfire Museum, June 7th – 12th, for a week-long celebration of native plants, featuring medicine-making, natural dyeing, wild foods cooking, plant walks, and even a few virtual events! Learn more at www.foxfire.org/events.

A natural dye pot of early spring blooms.

And remember, you should never harvest or use a plant without consulting a professional. Many plants used in herbal medicine can cause severe reactions if not handled properly. Please also consult the USDA for information on sustainable harvesting and the conservation status of native plants: https://www.fs.usda.gov/.