In celebration of Black History Month, we are featuring stories from our archive that capture black experiences in Appalachia. Each week in February, we will highlight one individual who shared their story with Foxfire high school students.

Our third featured interview is with Viola Lenoir, who was interviewed in 1981 at her home in Macon County, North Carolina. Viola shares conflicting images of race relationships; she remembers her warm and happy childhood with a white woman but contrasts this with traumatic accounts of lynchings in town. As you read, bear in mind this is the perspective Viola chose to share with Foxfire and is the story she wants you to hear.

Foxfire student Connie Wheeler describes meeting Viola:

Viola greeted us with a smile and warmly invited us into her home. Although she had never been interviewed before, she didn’t show a single sign of being a beginner. Viola, with all her warmth and friendliness, led us through the interview expertly and also taught us many new things. We focused our minds back to a century ago when things were so very different but seemed like present reality to us.

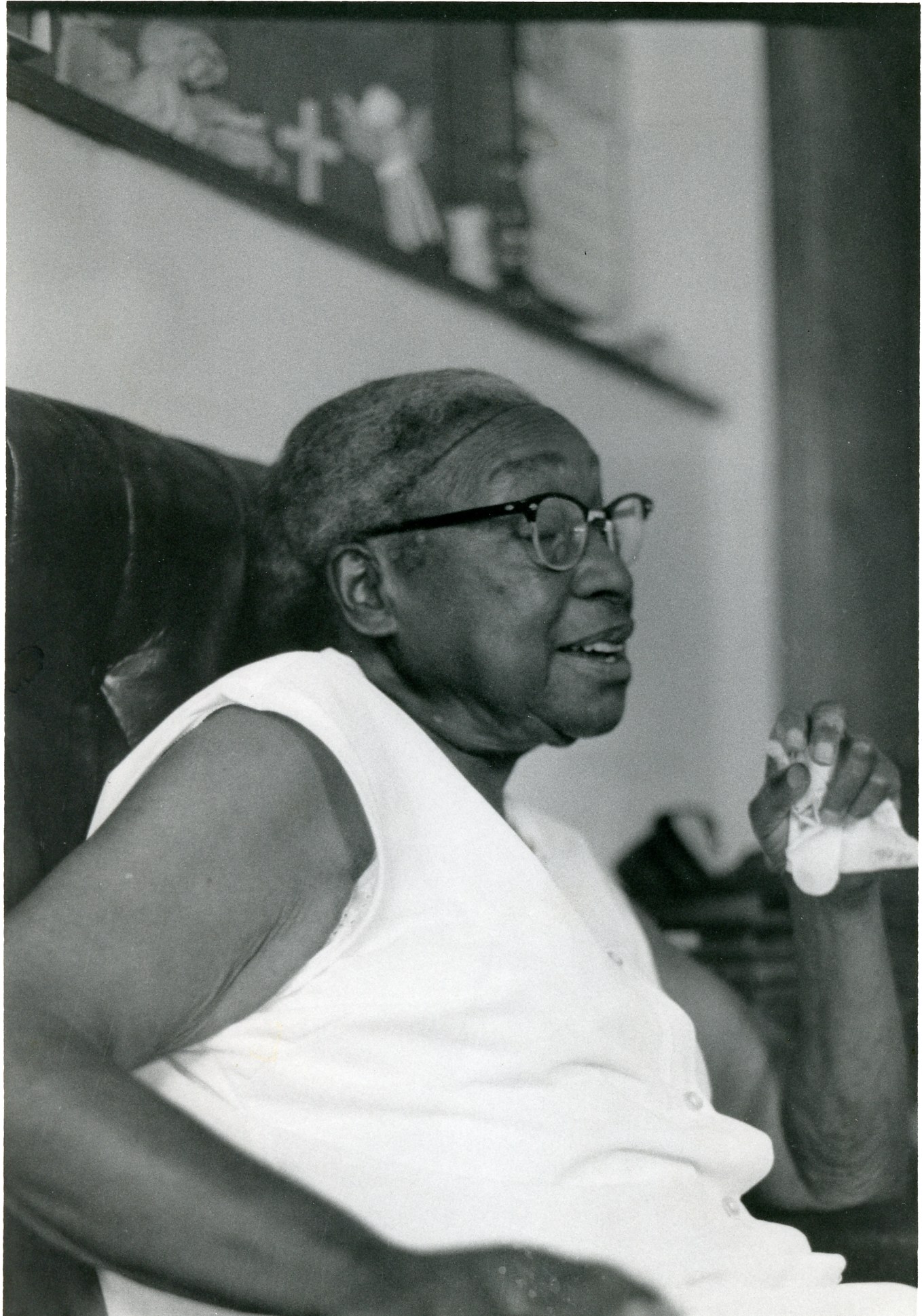

Viola Lenoir during 1981 Interview.

My grandmother on my daddy’s side was full-blood African. The white people separated her and her husband. They brought her to the United States and left him in Africa. Her first child was born over here in the United States. She wasn’t quite as tall as I am, but she was twice as big. That’s the fattest woman you ever seen! She could work but she couldn’t read or write. She did common labor, like cut wood, saw wood, mind babies, cook, and work in the cornfield.

I don’t know what tribe of Indians my mother’s mother came from and I don’t know where she came from. She came from Georgia to here [Macon County, North Carolina]. Her husband died and left her with four children, two boys and two girls. They were practically Indians. You see, my race is mixed up—Africans and Indians.

Anyway, I just can’t give no account of her, but I do know she couldn’t read and she couldn’t write and my daddy’s mother couldn’t either. I used to read to her on Sunday evenin’s after Sunday school and I did the same thing for my mother’s mother. They were just tickled to death when I got to where I could read.

My daddy couldn’t read. He wouldn’t go to school because he didn’t like it. If he went to school, he’d have to be quiet and couldn’t run rabbits or fish! Neither one of my uncles could read and write because they wouldn’t go to school either. They’d work good, though. They stuck with their parents in a farming business.

My mother could cook and she was a practical nurse. She got her nurse’s training just by going on calls with doctors. She had an eight-grade [education]. She was one of the first bunch of colored people that got religion and education.

We didn’t talk about slavery. We just talked about how good people was to us. As I was big enough to go into the third grade, this white woman come and took me away. My mother let me go on account of this stomach. We were practically on starvation! This woman, Miss Kelly, offered to take me to stay with her. She also fed my daddy and mama and brother.

Miss Elizabeth Kelly

So I was with Miss Elizabeth Kelly the beginning of my young life. She was a schoolteacher. She taught me up to the seventh grade. That’s all the education Viola has, but I’m just as proud of it as if I’d went to a thousand colleges.

Miss Kelly taught me in her bedroom. I slept in that bedroom and I dressed in that bedroom. She scared me half to death the first time she put me in a tub of water. I hadn’t been used to a bathtub; I didn’t know nothing about water and lights. We had kerosene lamps, but she had electric lights. Lord, I thought I was somebody in that place.

She wouldn’t let me wear colored dresses; I had to wear white ones. You see, I was colored, so she wanted me to have white. She said it made me look better. I stayed with her til I was 23 years old.

Miss Kelly was a good friend hat I could trust. If I got messed up with my figures, I’d take ‘em to her and she would work ‘em out for me. And I trusted her and I loved her just like I did my mother; she felt just like Mama to me. I had two homes; one with Miss Kelly and one with my parents.

And talk about holding something against the white people? Some folks may can—I can’t! They saved my life, my parents and my brother. We would have starved to death if it wasn’t for her. I tell you I just can’t give white people no bad name. I swear I can’t.

I always thought that the white people couldn’t be bad. Anybody can be bad if they want to, but I didn’t think they could because Miss Kelly and her family were so good to me. I just thought all white people were like that. All the friends I’ve met that were white would treat me just like she did. I could go downtown and drink juice in the drugstore [just like the white people]. So I just don’t think about the mixing or fighting between the whites and the colored. When it came to touching you and beating you up and cussing you out, I just don’t know nothing about that kind of stuff.

They hung two or three Negroes here for going with white women. They hung ‘em where the twon bridge is. That was the hanging place. Nobody didn’t see the men that were hung except the ones that did it. When they hung the last one, I was married. You see, the black men would slip and do these things and the women would slip around and have these men. But you didn’t know about it until you saw it in the paper. They didn’t do anything to the white women. But the hangings really scared everybody.

I think Macon County’s colored have gotten sort of straightened out and could see—as this old man said—“between the trees.” I don’t think they’ve ever fought. The only thing that I know of is how the Indians once owned Macon County. I don’t know whether Macon County fought ‘em out or bought ‘em out. It happened before I was old enough.

Everywhere I worked, they treated me just like I was a baby. I honest-to-goodness can’t give Macon County, where I’ve been born and raised, a bad name for being against colored people.

When I was fifteen years old, I could go into a kitchen and cook like a grown woman. I guess that’s what led me to working in hotels.

I caused myself to be a good Christian. You folks don’t know how proud I am that I can grab your hand. You don’t know what it is to go in a church with only five or six people there. We need all these people that move in here—white and black. We need ‘em to join with us to help us. I told the bishop that the church wasn’t built for colored. It was built for people. I asked two or three of these elderly white men what they thought of mixing with us. And each one said it was alright, that he couldn’t see any difference, just differences in color. I said, “Well, I’m about the blackest one in here and I won’t rub off on you.”

I feel good at my age when I think what I had to come through. I’m sure you just don’t know. I had some rough days and some rough weeks, but I’ve had a lot of good ones too.

Read the rest of Viola’s story in Foxfire 8